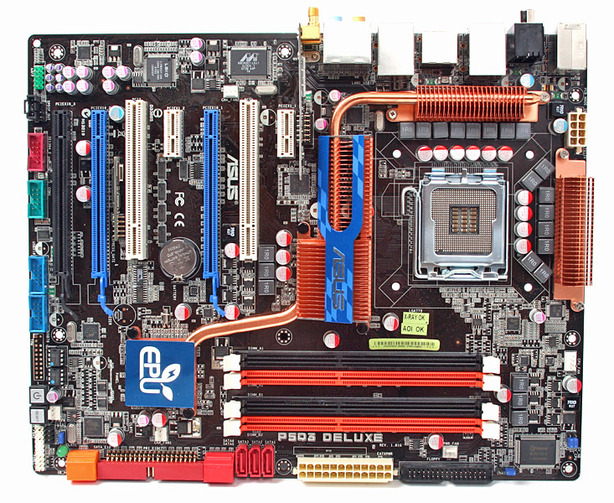

First Look: Asus P5Q3 Deluxe WiFi-AP @n

Manufacturer: AsusAs the Intel P45 Express chipset launch marches ever closer, Asus hooked us up with one of its premium P45 motherboards for a quick sneaky look. We’ve looked at a couple of P35 Asus boards this last year, some of which turned out very well, and others kind of crazy.

The new P5Q3 Deluxe WiFi-AP @n more closely reflects the X38 P5E3 Dexlue WiFi-AP @n we looked at late last year in terms of features – it has 802.11n WiFi integrated into the board—something no other manufacturer features—and, what’s more, EVERY P45 board in Asus’ range now features Splashtop. For those unaware of Splashtop, it’s an embedded Linux that runs from an onboard solid state micro-drive that allows ultra fast access to the Internet and Skype.

While the Asus EPU isn’t new, it has now been expanded to cover the chassis, graphics, hard drive, memory and the chipset as well as the CPU. This “EPU-6 Engine” is still essentially software driven with some hardware control and it's pretty much like a more advanced version of Nvidia’s ESA system, but this time with power management and more advanced overclocking options thrown in for good measure.

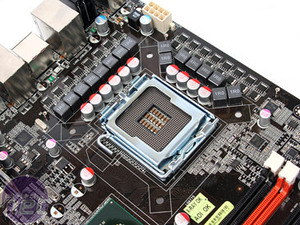

Asus also features a “16 phase power system” – the box art shows how it’s even cooler than six or twelve phase systems. Asus uses smaller chokes and two Power-PAK MOSFETs on the top and the single driver IC on the reverse. In comparison, Gigabyte boards feature a "virtual" 12 phase design: there are 12 (larger) chokes and 24 Power-PAK MOSFETs to accompany them, but they only have six driver ICs on the back and its (first generation) DES software makes jumps of two phases at a time. However, these driver ICs are twice the size of Asus' and working in pairs is logical if you consider CPU cores work in pairs.

The company is also only just now using the Low RDS(on) MOSFETs that Gigabyte has used in the past, however Asus claims that its solid aluminium capped Fujitsu RE polymer capacitors are better than Gigabyte’s solid aluminium Fujitsu ME polymer capacitors by a few thousand hours and can resist higher temperatures. Dare I even refer them to my article? Do us a favour guys – stop splitting hairs and look ahead instead of sideways.

We talked in depth with Asus about how many phases was enough and we're still a little unconvinced. Asus' EPU still does not handle the power phase switching with the same finesse as Gigabyte’s Dynamic Energy Saver system, the new EPU still only flicks between four and sixteen stages – idle and load (compared to four and eight like previous). However we know that the CPU frequency and voltage changes in multiple steps when the EPU is enabled.

Asus explained that even though there’s a bigger dip in the crossover, overall the jump from eight to sixteen phases didn't warrant that large an efficiency gain and that overall it had a greater efficiency than Gigabyte. As ever, we remain sceptical about PowerPoint evidence, however what Asus did say that what we had worried about in the past was that only one phase switching, this causes fewer power spikes as different numbers of phases are being used. Essentially Asus claimed to see more stability and less stress being placed on the CPU. But then again, the Asus phase jump is now doubled from two fold to four fold, not just a couple of phases every time.

On Gigabyte's 12 phase design with its DES system running, we’ve never seen more than eight to ten phases being used even with an overclocked quad-core, so are 16 phases necessary? What is the optimal running load – how does it handle the difference between dual-core and quad-cores? What has a greater effect – constant switching or switching more phases at once? We will investigate to see the differences and actual power saving during the full review.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.